The Americans as Cultural Revolt

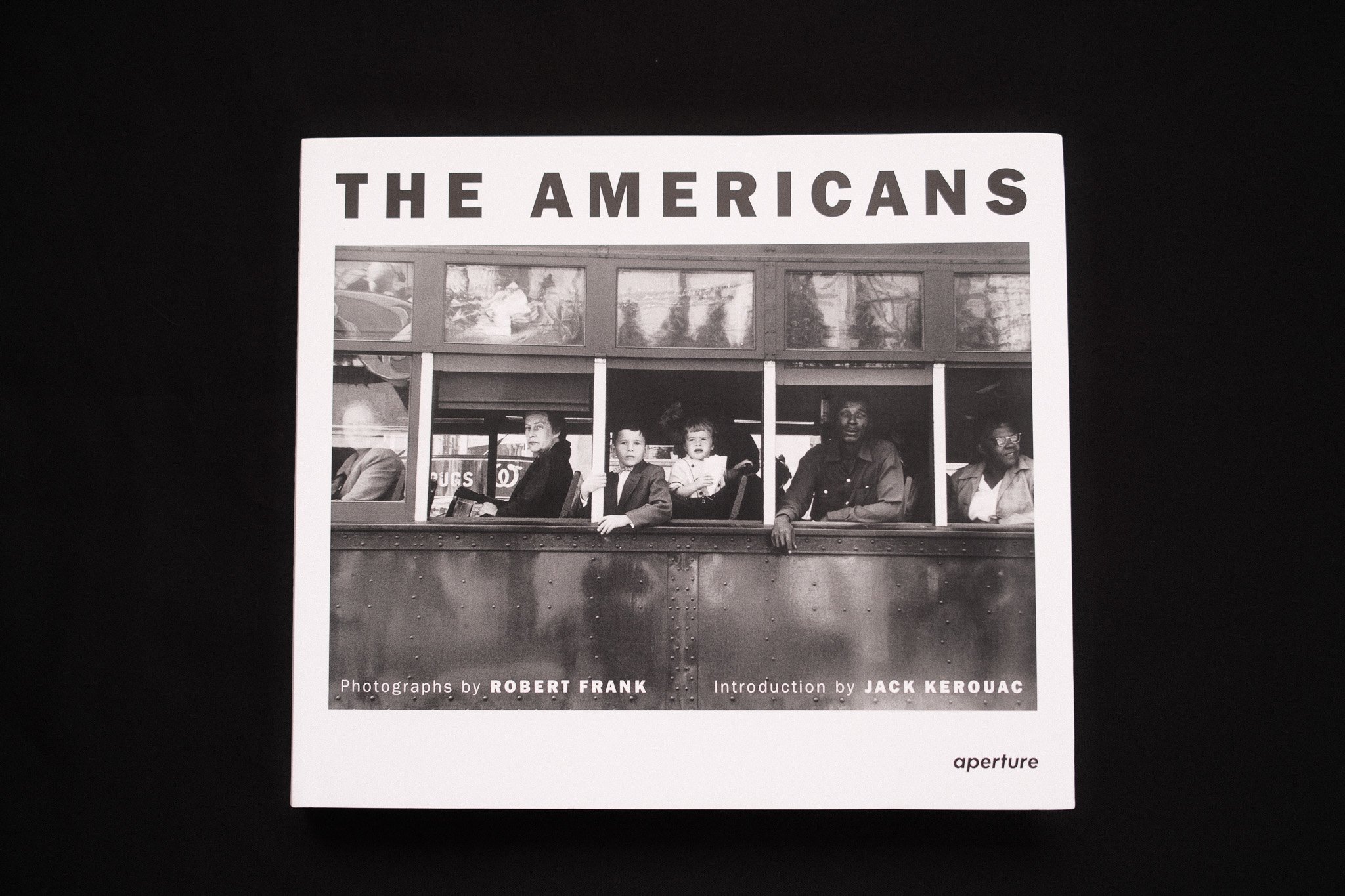

When I first opened The Americans, I didn’t know whether I was more eager for Robert Frank’s photographs or Jack Kerouac’s introduction. As a photographer, I wanted to dive straight into the images. As a writer, I wanted to hear Kerouac set the tone. It’s rare for one book to pull me both ways at once.

The opening sentences of Kerouac’s foreword didn’t sound like the voice I knew from On the Road or The Dharma Bums. They were restrained, almost cautious. But soon the language loosened, phrases rolling forward like a train over open country. He didn’t explain Frank’s pictures. He matched them. The words moved the way the photographs did: quick, unvarnished, alive.

“Madroad driving men ahead—the mad road, lonely, leading around the bend into the openings of space towards the horizon Wasatch snows promised us in the vision of the west, spine heights at the world’s end, coast of blue Pacific starry night—nobone half-banana moons sloping in the tangled night sky, the torments of great formations in mist, the huddled invisible insect in the car racing onward, illuminate—The raw cut, the drag, the butte, the star, the draw, the sunflower in the grass—orangebutted west lands of Arcadia, forlorn sands of the isolate earth, dewy exposures to infinity in black space, home of the rattlesnake and the gopher…” From Kerouac’s introduction

Frank’s America wasn’t the polished postcard version. His lens caught diners lit by bare bulbs, segregated sidewalks, faces half-turned toward something outside the frame. He framed the parade from the curb instead of the grandstand. He looked through the windshield instead of from the passenger seat. The sequence has its own rhythm, a pull between intimacy and distance, as if you’re drifting across the country without ever arriving.

In the 1950s, this was a kind of visual heresy. Magazine photography was staged, richly lit, crafted to affirm a national image of prosperity and unity. Frank did the opposite. His frames were grainy, tilted, sometimes awkward in ways that felt deliberate. He left space for imperfection, let moments breathe (or suffocate) inside the frame. It was documentary work that refused to flatter, and that refusal was part of its rebellion.

Kerouac understood that rhythm and defiance. His sentences bent toward the same truths Frank’s camera caught: the beauty and exhaustion of small towns, the tension between celebration and isolation, the ache of the open road. Together, they offered an unfiltered portrait of America at a crossroads, post-war optimism colliding with racial segregation, widening class divides, and a restless undercurrent that would soon break into open revolt.

When The Americans reached U.S. shelves, critics were not generous. The photographs were called bleak, even unpatriotic. One review dismissed them as “a sad poem for sick people.” That reaction was part of the work’s power. Frank’s outsider perspective, paired with Kerouac’s Beat sensibility, refused to sell an easy story. They weren’t interested in telling America what it wanted to hear. They wanted to show it to itself: light and shadow, pride and fracture lines.

Seventy years later, the tension in Frank’s photographs hasn’t eased. Faces change, fashions change, but the undercurrents remain. Stand on any street corner and you can still see them: wealth and poverty, inclusion and exclusion, celebration and protest, all compressed into a single frame.

In Frank’s day, the discomfort came from showing a side of America that marketing preferred to ignore. Today, it often comes from realizing those divisions have endured. We scroll past images instead of leafing through them, but the questions they raise still demand an answer. It’s a reminder that technology changes the pace, but not the need, for deep seeing. You have to stop long enough for the frame to tell you something true.

Modern politics runs on imagery as much as language. A protest sign, a candid exchange between public figures, a shaky cellphone video, all can shift the conversation as much as a speech. That’s the power of producing rather than consuming: creating a frame that carries meaning, instead of letting meaning be handed to you already filtered. Frank’s work reminds us that a single photograph, honestly made, can cut through the noise and leave a mark.

For photographers, the lesson is liberating and demanding: you don’t need perfect conditions, only an unflinching eye and the will to press the shutter at the right moment. For viewers, the challenge is to see without projection, to notice what’s there, not just what fits our story. That’s a kind of freedom too: the freedom to see without needing the picture to flatter us.

Frank and Kerouac’s collaboration was a prelude to the visual culture we inhabit now. They paired image and word to make something neither could have achieved alone. In an age where photographs travel faster than their context, that pairing, and that honesty, may be more necessary than ever.

I came for the photographs and stayed for the words. At first, Kerouac’s opening felt unfamiliar. But soon, there he was: syncopated, streetwise, leaning in like an old friend. Frank’s images were the same way. They waited. And then they hit you.

It made me think about my own work, the way a photograph changes when words hold it, and how the right words can sharpen a frame without crowding it. Frank and Kerouac weren’t just making art. They were building a conversation that asked something of the viewer. They were producers of meaning in a world eager to sell easier versions of the truth. That conversation is still worth hearing.

Thank you for reading. If you would like to explore more in-depth content, I invite you to check out my book, "Wander Light: Notes on Carrying Less and Seeing More." It helps support this web page and enables me to continue providing you with more content. Get your copy here.