Bad Bunny Wasn’t Divisive. The Reaction Was

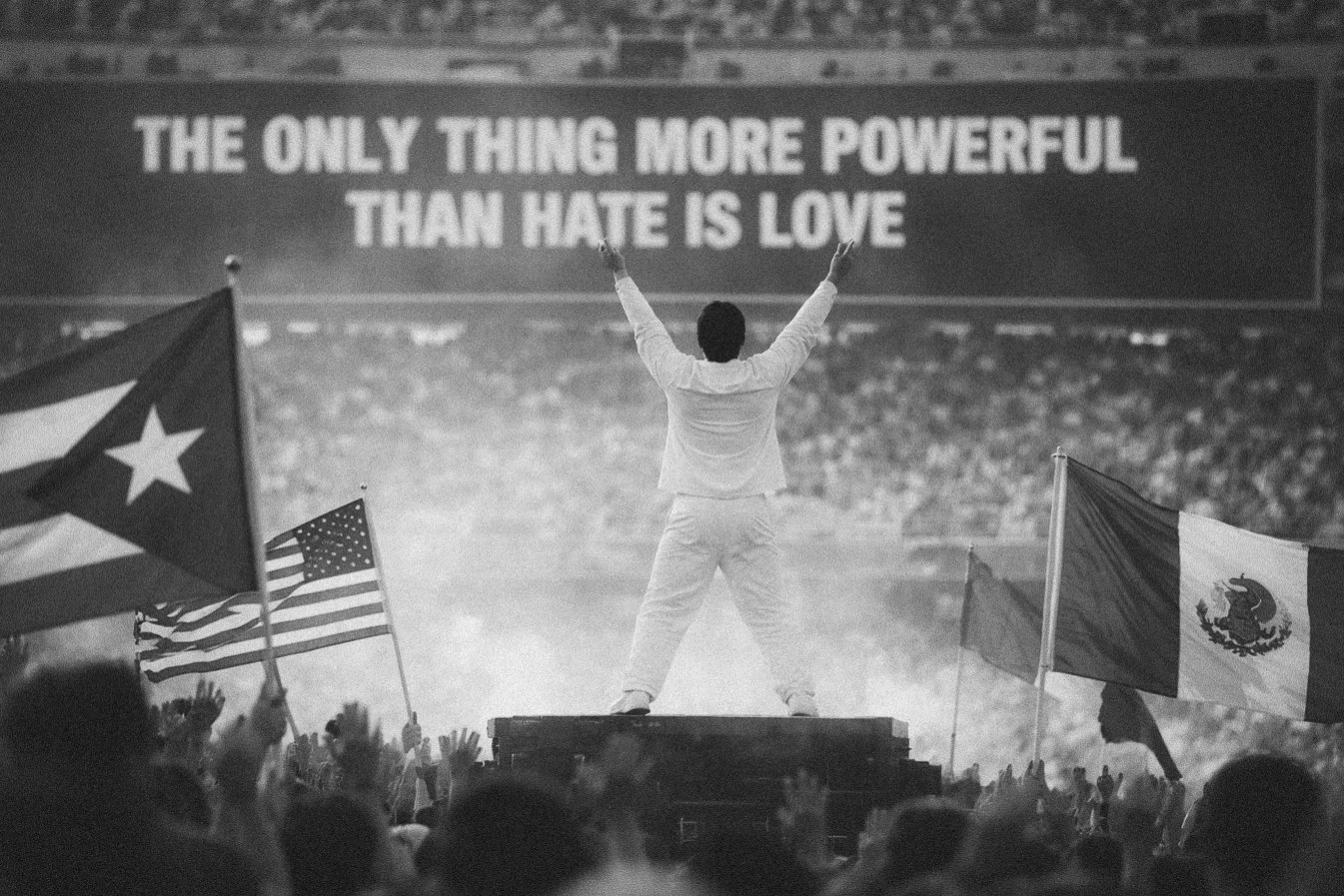

A man stepped onto the largest stage in American entertainment and sang about love. He sang in Spanish, the language he grew up with. Behind him, a simple message filled the screen: the only thing more powerful than hate is love. He spoke of America as a shared hemisphere, naming the countries that stretch from north to south as part of a single story. The performance was calm, celebratory, and expansive. Yet it was quickly described as divisive.

That judgment did not wait for the show to end. In fact, much of it did not wait for the show to begin. Criticism had already formed in advance, aimed not at any specific lyric or moment, but at the presence itself. The expectation was set early. This would be political. This would be a provocation. The verdict arrived before the music did.

After the performance, the president added his voice to the backlash, dismissing the show in blunt, contemptuous terms and reducing it to a complaint about language and national insult. The reaction focused less on what was said than on the fact that it was said in Spanish, by an artist who refused to translate himself into something more familiar. Love was not engaged on its own terms. It was waved away as offense.

Nothing in the performance called for exclusion. No group was targeted. No enemy was named. The songs moved through themes that were easy to recognize even without translation: joy, memory, desire, cultural pride, autonomy, and community. Some were celebratory. Some were sensual. Some reflected on history and place. None were about hate. None called for harm. None asked anyone else to disappear.

Some songs insisted on autonomy and respect, echoing the spirit of a woman dancing freely without harassment. Others lingered on nostalgia, on the ache of wishing you had taken more photos with people you loved before time slipped away. A few carried political weight, reflecting on Puerto Rico’s history and identity, but they sounded more like testimony than accusation. The emotional arc of the performance moved through celebration, longing, pride, and resilience. It felt human long before it felt political.

That gap between content and reaction matters. When criticism precedes the message, it cannot be a response to what was said. It is a boundary drawn in advance. A warning about who is allowed to occupy the center, and under what conditions.

This is where the word divisive does its real work. It sounds neutral. Responsible. Concerned with harmony. But in practice, it functions as a tool of control. Labeling a message divisive allows it to be dismissed without engaging its substance. The accusation becomes the argument. No rebuttal required.

Resistance music has lived inside that dynamic for decades. In the late twentieth century, listeners turned up the volume on N.W.A. as they described encounters with policing and life under constant surveillance. Songs like “Fuck tha Police” were called dangerous or hateful, yet many who listened did not hear a call for chaos. They heard frustration finally spoken out loud. Years later, Rage Against the Machine filled arenas with songs about economic power, state violence, and the machinery of control. Fans who now feel uneasy about modern resistance once shouted those lyrics back at the stage, not because they hated their country, but because they wanted it to live up to its promises.

Earlier still, artists such as Bob Dylan and Joan Baez questioned war and national myth through folk music that was once accused of weakening American resolve. Those songs asked listeners to reflect on violence carried out in their name. At the time, they were labeled divisive. Today, many people remember them as courageous and necessary. Memory softens controversy. What once sounded radical begins to feel inevitable.

The halftime performance followed that same script. Singing in Spanish was treated as a political act. Naming America as larger than a single border was read as provocation. Even a message explicitly centered on love was interpreted as an attack. The reaction revealed an assumption that unity depends on familiarity, on dominance going unchallenged, on certain voices remaining background noise.

What unsettles people in moments like this is not division, but decentering. When a culture has long treated one voice as default, any widening of the frame can feel like loss. Inclusion sounds like displacement. Shared humanity sounds like accusation. The word divisive arrives to restore order, to push the boundary back where it was.

Music becomes the battleground because it reaches people before politics has time to sanitize it. It moves through memory. It reminds listeners of who they once were, of the songs they sang when they were younger and less certain about where authority ended and conscience began. Many of the same people who now feel uneasy about a Spanish-language performance once found their own sense of identity reflected in music that unsettled the cultural center.

The halftime show did not divide the audience. It exposed a division that was already there. One side heard a familiar message in an unfamiliar voice and recoiled. The other heard something ordinary and human. That difference had nothing to do with melody or rhythm. It had everything to do with who is allowed to speak without being accused of disruption.

Calling love divisive is not a critique of art. It is a confession. It reveals how narrow the definition of unity has become, and how quickly it collapses when asked to include more than it was designed to hold. Resistance music does not create that fragility. It reveals it.

And it will continue to do so, as long as voices outside the center keep stepping forward, singing in their own language, and refusing to accept that silence is the price of belonging.