The Artist and What We Choose to See

Artists have long stood at the forefront of social change, not simply as commentators on their societies, but as forces that shape what those societies are willing to see. From Picasso’s response to the violence of Guernica to the unsettling clarity of Baldwin’s prose or the quiet insistence of Dorothea Lange’s photographs, creative work has repeatedly altered the boundaries of public awareness. Art does more than reflect the world as it is. It shifts attention, reframes experience, and, in doing so, changes what a culture can no longer ignore.

What this history suggests is something slightly uncomfortable. If art has the power to redirect attention, then it cannot be treated as neutral decoration or private expression alone. The act of creating always carries a choice about what deserves to be seen, remembered, or questioned. And once that becomes clear, it raises a larger question about the role of the artist: whether the task is simply to create something compelling, or whether creative work inevitably carries a responsibility to illuminate what society might otherwise leave in the dark.

Again and again, the artists who endure are those who made something visible that had previously remained abstract, distant, or easy to ignore. Their work did not simply express opinion. It altered perception.

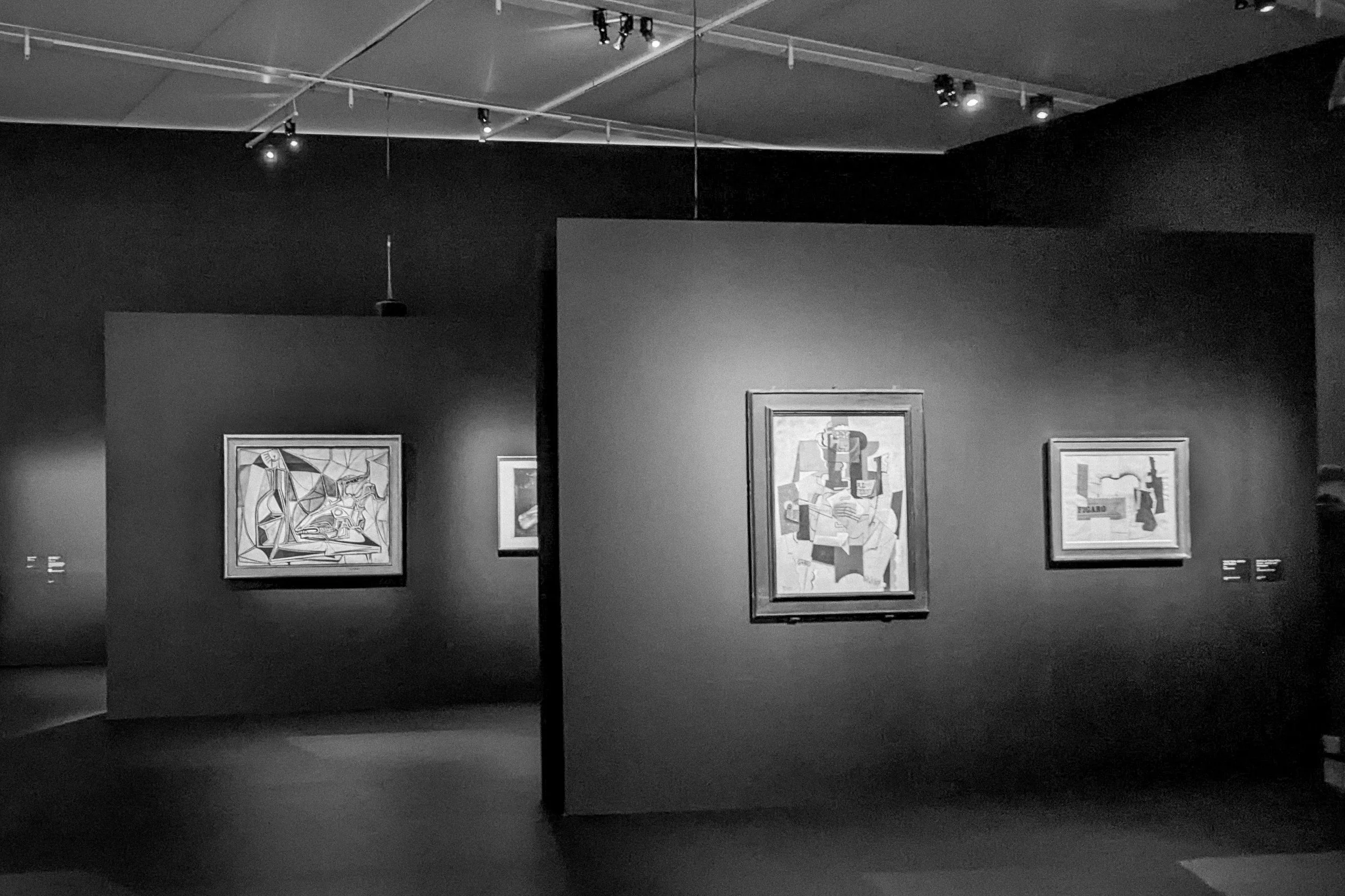

Picasso’s Guernica did not introduce the world to the existence of war. What it did was collapse the distance between battlefield and observer. By rendering civilian suffering in fractured forms and stark contrasts, he forced viewers to confront violence as a human experience rather than a strategic event. The painting did not argue in words. It made indifference harder to sustain.

Diego Rivera approached the same problem from another direction. His murals pulled labor, class struggle, and industrial power out of political discourse and placed them directly into public space. These were not images meant for private contemplation. They were assertions about whose lives mattered enough to occupy the walls of civic buildings. In doing so, Rivera made social hierarchy visible in places that had previously masked it behind architecture and ceremony.

Frida Kahlo’s work shifted attention inward rather than outward, yet the effect was no less political. Her paintings insisted that identity, gender, illness, and personal history belonged within the domain of serious art. At a time when the private self was often treated as apolitical or decorative, Kahlo made the interior life inseparable from the social world that shaped it. The result was a body of work that challenged viewers to see the personal not as an isolated experience, but as something formed within larger structures of culture and power.

Photography, perhaps more than any other medium, has carried this capacity to redefine what a society notices. Dorothea Lange’s images of the Great Depression did not create poverty, but they made its human cost unavoidable to audiences who might otherwise have encountered it only as statistics or distant reports. Her photographs condensed vast economic realities into individual faces and gestures, transforming abstraction into recognition.

Gordon Parks extended this tradition by turning his camera toward the racial structures embedded in American life. Working within mainstream publications, he produced images that forced readers to confront conditions that had long been normalized or overlooked. Parks demonstrated that even within established institutions, an artist could reshape what those institutions allowed their audiences to see.

Writers have often played a similar role. James Baldwin’s essays and novels stripped away the language that allowed societies to soften or evade their own contradictions. His work did not simply describe injustice; it exposed the psychological and moral frameworks that sustained it. In doing so, Baldwin compelled readers to confront realities that polite discourse preferred to leave unnamed.

Even Hemingway, whose style is often associated with restraint rather than overt social critique, operated in this same territory. His writing made emotional cost visible in ways that avoided moral instruction but left little room for illusion. By presenting war, love, and disillusionment with stark clarity, he showed how artistic precision itself can function as a form of revelation.

What unites these figures is not a shared ideology or method, but a shared effect. Each redirected attention. Each made something harder to overlook. And in doing so, each expanded the boundaries of what their culture could no longer pretend not to see.

If artists have repeatedly shaped what their societies are able to see, then the idea of neutral art becomes difficult to sustain. Creative work may not always begin with an explicit political intention, but it inevitably participates in directing attention. Every choice about subject, framing, tone, and emphasis carries an implicit statement about what is worth noticing.

This is why the distinction between art that “engages” social issues and art that simply pursues beauty can be misleading. Beauty itself is not neutral. What a culture chooses to represent as beautiful, dignified, or worthy of attention often reinforces existing values just as powerfully as overt political messaging. To depict only harmony, only stability, or only the already recognized can quietly affirm the structures that determine whose lives are seen and whose remain peripheral.

Silence, in this sense, is not absence. It is a form of participation. What artists choose not to show can shape collective understanding as strongly as what they place at the center of their work. Entire social realities can remain culturally distant not because they are invisible in themselves, but because they are rarely given sustained artistic attention. When that attention does arrive, the effect can feel sudden or even disruptive, though the underlying conditions may have existed all along.

The influence of art, then, lies less in persuasion than in perception. Artists rarely change minds through argument alone. What they often change is the field of awareness within which arguments take place. By clarifying experience, by compressing complex realities into images or narratives that cannot easily be dismissed, they alter what a society recognizes as real, immediate, or morally significant.

Seen this way, the responsibility of the artist may not rest primarily in advocating particular positions, but in recognizing that creative work inevitably shapes the horizon of what others are able to see. The question is not whether art influences culture. It is whether the artist acknowledges that influence and chooses subjects, perspectives, and forms with that awareness in mind.

Seen in this light, the question of artistic responsibility becomes difficult to treat as purely theoretical. It begins to surface in the everyday choices of practice, often long before it is articulated directly. For much of my time as a photographer, my focus rested on the pursuit of a strong image. Composition, atmosphere, timing, and visual cohesion felt like sufficient aims in themselves. If the photograph held together formally, it seemed to have fulfilled its purpose.

There is nothing trivial about that pursuit. Craft matters, and the ability to see clearly is not separate from meaning. Yet over time, it became harder to ignore a subtle dissatisfaction with images that functioned only at the level of appearance. They could be successful visually and still leave the sense that something remained unexamined, that the work had stopped at the surface of experience rather than pressing into what shaped it.

It was through writing that this tension first became explicit. Essays provided a space to explore questions about culture, autonomy, and the systems that structure everyday life. In that context, the role of attention became clearer. Writing does not simply record thought; it directs it, deciding which aspects of experience deserve to be named and which assumptions should be tested.

Photography began to feel connected to this process in ways that had not been obvious before. The act of choosing where to point a lens, what moment to preserve, and what to leave outside the frame carries the same underlying question as writing: what is worth noticing? Even when the subject is ordinary, the decision to isolate it visually can suggest that it carries meaning beyond its immediate appearance.

What emerged from this shift was not a move toward overtly political imagery, nor a rejection of craft. Instead, it was a growing awareness that creative work, whether visual or written, participates in shaping attention. Once that recognition takes hold, it becomes difficult to treat any artistic choice as entirely neutral, even when the work itself remains understated.

If creative work inevitably shapes what people notice, then the question of responsibility becomes less about ideology and more about awareness. The artist is not required to adopt a particular political position, nor to treat every work as a declaration. Art that reduces itself to messaging alone often loses the very qualities that make it capable of altering perception in the first place. Yet the alternative, pretending that artistic choices exist outside cultural influence, is equally unconvincing.

Responsibility, in this sense, does not mean that every artist must seek to provoke or persuade. It may lie instead in the willingness to recognize that creative attention is never without consequence. What is framed, described, or emphasized acquires a form of cultural weight, while what remains consistently outside the frame risks being treated as marginal or unreal. The influence of art emerges not only from what it argues, but from what it allows to be seen at all.

This understanding reframes the role of the artist in a quieter but more durable way. The task is not necessarily to instruct an audience or to advocate a program, but to notice carefully and choose deliberately. It involves asking, often implicitly, whether the work clarifies experience or merely repeats familiar surfaces, whether it opens perception or simply reinforces what is already comfortably understood.

Many of the artists who endure seem to share this quality. Their work does not always announce itself as socially engaged, yet it alters how people encounter the world afterward. They shift the scale of what feels immediate, what feels human, and what feels worth confronting. That shift, once it occurs, often proves more lasting than any explicit argument.

Seen this way, the responsibility of the artist may be less about changing the world directly and more about refusing to look at it carelessly. Creative work becomes meaningful not because it guarantees transformation, but because it participates in defining the field of awareness within which transformation becomes possible.

If the history of art suggests anything, it is that creative work rarely leaves the world unchanged. Even when it does not seek to persuade, it has the capacity to alter what feels immediate, what feels human, and what feels worthy of attention. Once an image, a sentence, or a body of work shifts perception in that way, the effect often outlasts the circumstances that produced it.

This does not mean that artists control how their work will be interpreted, nor that they can predict its influence. Cultural attention moves in unpredictable ways, and many works that once seemed urgent fade quietly into the background. Yet the possibility remains that any creative act participates in shaping what others notice, what they remember, and what they begin to question.

For the artist, this realization does not necessarily lead to louder work or more explicit intention. It may instead encourage a more careful relationship to subject, to framing, and to the assumptions carried into the act of creation itself. If art helps define what a society sees, then the act of making it cannot be entirely detached from the act of noticing the world with care.

The responsibility of the artist, then, may not lie in producing declarations or answers. It may lie in the quieter discipline of attention, in the willingness to see fully and to render that seeing honestly. From that process, influence follows where it will.

Art does not change the world simply by existing. But it does help determine how the world is seen. And that, more often than not, is where change begins.